With my late older brother’s birthday, October 5th, coming up, I’ve been thinking about him.

Eddie Davis was three and a half years older, and although we agreed on most things, large and small, we would often strive to find a small point just big enough to argue about.

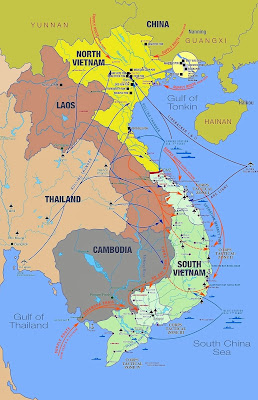

A case in point was the Vietnam War.

No, we didn’t argue about America’s role in the war, or even the disastrous political and military decisions made throughout the war. We both agreed that we should have gone all in and won the war outright.

No, our disagreement had more to do with the traditional Army-Navy rivalry.

Our late father, Edward Miller Davis, served in both the Army and the Navy. He had enlisted in the U.S. Army prior to World War II and was stationed in Panama. He spent a good bit of time guarding the Panama Canal and chasing bandits through the hills.

He left the Army, married our mother and had our older brother Bill and sister Jane, and worked as a lineman. When World War II broke out, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy and became an Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) frogman, even though he was draft exempt due to prior service and having a wife and children.

So our family had connections in both branches of the service.

My brother Eddie served in the U.S. Army at Chu Lai in South Vietnam in 1968 and

1969. He was a tower commander on the perimeter of the outpost.

He told me that conditions were so primitive and basic at Chu Lai that years later while watching the TV series MASH, he would look at the army camp and mutter, “Luxury, luxury.”

He told me that after taking a shower, he would walk back to his hooch through the mud, heat and bugs, feeling that he needed another shower. He had other complaints about the harsh conditions at Chu Lai, not the least of which were the Viet Cong rocket and mortar attacks.

I enlisted in the U.S. Navy and served on the USS Kitty Hawk as the aircraft carrier performed combat operations on “Yankee Station” in the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of North Vietnam in 1970-1971.

The aircraft carrier was a floating city and the 5,500 sailors aboard had all of the amenities of home save female companionship. (That was remediated with our frequent port of calls to Subic Bay and Olongapo City in the Philippines, and R&R visits to Sasebo, Japan and Hong Kong).

The ship’s cooks served three

full fairly good meals a day, and while on Yankee Station, they also served

“Midrats,” midnight rations, for the guys on the Midwatch. Midrats offered

grilled hamburgers, hotdogs, and French Fries. I loved Midrats.

We were the first warship to have cable TV and radio in every compartment of the ship and a new film was shown every day three times a day. We had our own ship’s newspaper (where I wrote my first news articles). We also had a store on the ship called a “Gedunk,” where a sailor could buy sodas, snacks and treats. We also had a gym and a library.

We had a clean ship to live in, which was important to me. (I joined the Navy because of clean ships, not realizing that I would be one of the seamen who had to clean it).

The Vietnam heat and humidity was brutal, even at sea, so we were blessed with air-conditioning throughout the ship.

So this was our bit of discourse.

My brother, partly in jest, often dismissed the Navy’s efforts in the war, saying I served on a luxury cruise ship. In response, I would tell my brother that without naval air power and support, he and many other soldiers would be dead. He would nod in agreement, but in a few weeks’ time we would again be debating our war roles.

It was a long and tough combat cruise, but, admittedly, we certainly lived better than the soldiers and Marines “in-country” in South Vietnam.

As I noted often to my brother, this was no pleasure cruise. We worked long and hard hours – eight hours on watch/eight hours off watch every day.

For the pilots who flew combat sorties over North Vietnam and Laos, the war was a dangerous affair and the threat of being shot down and killed or becoming a POW was a real concern,

The aircraft carrier was too well protected by the battle group of ships and aircraft to face assault by the North Vietnamese, but the main concern was accidents.

The airmen serving on the flight deck during air operations, swiftly launching and recovering aircraft, experienced danger every day from deadly accidents. And the deck sailors faced dangers during underway replenishment (UNREPs), in which supplies and fuel were transferred from a supply ship and oiler to the carrier using lines stretched across the water from one moving ship to the other moving ship in the rising and falling waves of the ocean.

UNREP operations were tricky and potentially dangerous.

And with all of the bombs, missiles and jet fuel onboard the ship, we were always concerned with fires and explosions. While attending two fire-fighting schools in San Diego prior to sailing to Vietnam, I watched the flight deck films of the horrific fires and explosions on the USS Forrestal. I saw the sailors blown up, set on fire, and die.

At sea, a ship on fire cannot call the fire department. We are the fire department.

I served in radio communications, but I also served on a Damage Control Team. The teams were called out in emergencies to put out fires and save lives. We donned gas masks, helmets and fire-retardant jackets and manned the long water hoses and chemical extinguishers. We were called out several times during the cruise, but thankfully we did not encounter anything as major as the great Forrestal fire.

Another advantage of serving on a carrier was the warship had doctors and surgeons and a full surgical unit to deal with medical emergencies. And the ship also had a dentist aboard.

I had dental surgery while serving on the carrier and had my wisdom teeth removed. I was awake and alert for what seemed like hours as the dentist and his dental technician yanked, ripped and eventually extracted my wisdom teeth.

I don’t know how those four hands and the various instruments of torture (which originated from the Spanish Inquisition, I presumed) fit into my mouth.

“That was the hardest dental surgery I’ve ever experienced,” the dental tech told me as I sat in the chair heaving.

“Me too,” I mumbled through my swollen cheeks and bloody mouth.

But with the removal of my wisdom teeth, I did gain some wisdom – in the future I made sure I was gassed and knocked out whenever a dentist removed a tooth from my head.

So, although my late big

brother faced Viet Cong bullets, rockets and mortars, he never knew the horror

of having a Navy dentist rip wisdom teeth out of his head.

Happy Birthday and RIP, older brother and old soldier Eddie Davis.

Note: Below are photos of my brother Eddie Davis, my late father, me at sea, and photos from the 1970-1971 WESTPAC cruise:

R.I.P. Shipmate.

ReplyDelete