You can read the piece via the below pages or the below text:

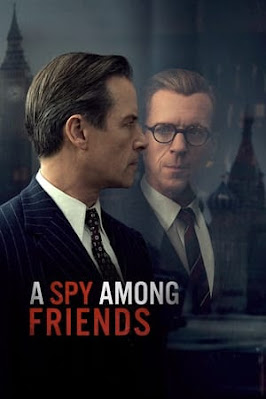

The six-part series, based on Ben Macintyre’s book, is well-made and has two strong leading actors, Guy Pierce as Philby, and Damian Lewis as Elliot. But one complaint is that the series is complicated and expects the viewer to be cognizant of the life and treachery of Philby at the start of the series. A second complaint is that the series injects a fictional character in the form of a woman MI5 interrogator, as well as several fictional events.

Still, those interested in espionage history and high drama will enjoy “A Spy Among Friends.”

“There is voluminous literature on Kim Philby, including the invaluable pioneering work of writers such as Patrick Seale, Philip Knightly, Tom Bower, Anthony Cave Brown and Genrikh Borovik,” Ben Macintyre wrote in the introduction of “A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal.” “But to many readers Philby remains opaque, like the Cold War itself., often alluded to but little understood. Moreover, in recent years the release of much previously classified material, along with authorized histories of MI5 and MI6, has shed new light on both that conflict and Philby’s place in it.”

Kim Philby was born in India

in 1912. His father was H. St. John Philby, a famous British Arabist and Middle

East scholar. Strong-willed and independent, H. St. John Philby despised

British imperialism, converted to Islam and advised Arab leaders. The father

called his son “Kim” after the child spy in Rudyard Kipling’s classic novel of

espionage in India.

Attracted to communism, Kim Philby was recruited by the Soviets in 1934. He attended Cambridge with the other recruited British spies who later became known as “The Cambridge Five” spy ring.

In 1936, he was working for an Anglo-German trade journal, (beginning his long-time cover as a journalist) and used the cover to report to his Soviets handlers on the Nazi German government. He went on to operate as a journalist in Spain in early 1937 during the Spanish Civil War and later became the London Times correspondent to Spanish Loyalist leader General Franco.

Urged by his Soviet handler, Philby joined the British SIS and became a penetration agent for the Soviets in 1940 during World War II. A year later, he was assigned to the counterespionage section dealing with the Iberian Peninsula, and in 1944 he was chosen to head up the newly created Soviet counterintelligence unit, Section IX.

From 1947 to 1949, Philby was chief of the British Istanbul SIS station. A rising star in SIS, Philby was then posted to Washington D.C. and became the British liaison to the CIA and FBI. He regularly swapped secrets as he lunched with the CIA’s counterintelligence chief, James Jesus Angleton, whom he first met in London. Philby was in an ideal position to pass secrets to the Soviets about the intelligence partnership between the British and the Americans.

Kim Philby was by all accounts intelligent, charming, and a very good professional intelligence officer. He was also what the British call a “rotter.” He was a serial philanderer and alcoholic who betrayed his wives, his friends and his SIS and American colleagues.

“I have always operated on two levels, a personal level and a political level. When the two come into conflict, I have had to put politics first,” Philby said in justifying his treachery to family, friends and country.

The end nearly came for Philby in 1951 when he discovered that fellow Cambridge spy and British Foreign Service officer Donald Maclean was suspected of being a Soviet spy. Philby sent Guy Burgess, another Foreign Service officer and Soviet spy to warn Maclean and arrange for his defection to the Soviet Union. Philby warned Burgess, a raging alcoholic and flamboyant homosexual, not to defect as well.

But Burgess did defect

with Maclean and suspicion fell on Philby as “The Third Man” in the spy ring

and the man who warned them. Philby was forced to leave Washington. MI5

interrogators were unable to prove Philby was The Third Man, and SIS senior officials

supported him, but Philby was forced to resign from SIS.

Philby was publicly

called "The Third Man" in Parliament in 1955. He was then publicly cleared by Foreign

Secretary and later Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, who spoke in Philby’s

defense.

When starling new

evidence confirmed that Philby was indeed a Soviet spy in 1962, his former SIS colleague

and friend Nicholas Elliot was sent to Beirut to confront him. Elliot offered

Philby a deal and Philby gave Elliot a signed confession. But rather than

return to the United Kingdom, Philby boarded a Soviet freighter and sailed to

the Soviet Union. The Soviets announced Philby’s defection, which embarrassed

the British government and SIS.

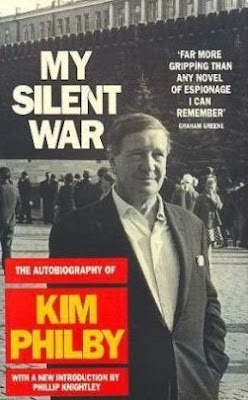

While in the Soviet

Union, Philby wrote about his life as a Soviet spy in the book, “My Silent

War,” which was no doubt co-written by the KGB. The book further embarrassed

the British government. In the book, Philby admitted to being a straight

penetration agent for the Soviets but denied being a traitor.

“To be a traitor,” Philby wrote, “One must belong. I never belonged.”

While speaking to East German Stasi officers in a 1981, Philby said the SIS failed to uncover him as a Soviet agent due to the British class system. He said that it was inconceivable to senior officers that that he, ‘born into the ruling class of the British Empire,’ could possibly be a traitor.

Kim Philby thought he

would be hailed as a Soviet hero and made a KGB general, but the Soviets were a

suspicious and untrusting lot, and Philby was placed in a Moscow apartment and was

basically sidelined.

Kim Philby became a

bitter alcoholic and lived the last 25 years of his life in Moscow, dying in

1988. He did not live to see the Communist Soviet Union, the evil empire he served

all of his life, fall in 1999.

In addition to the many nonfiction books about Kim Philby, he was also the inspiration for two fictional characters created by two former SIS officers-turned-novelists. Graham Greene, who worked for Kim Philby in SIS during World War II, wrote “The Human Factor,” which featured a double agent much like Philby.

John le Carre, who served briefly in SIS, wrote the brilliant spy thriller, “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy,” which was about a senior SIS officer and Soviet double agent based on Philby. The novel spawned a fine TV miniseries and a feature film.

Former CIA Director Allen Dulles called Kim Philby “the best spy the Soviets ever had.” British historian Anthony Cave Brown, who wrote “Treason in the Blood: H. St. John Philby, Kim Philby and the Spy Case of the Century,” called Kim Philby “quite possibly the greatest unhanged scoundrel in modern British history.”

Paul Davis, a long-time

contributor to the Journal, writes the IACSP online Threatcon column.

No comments:

Post a Comment